A recent survey of PhDs found that many researchers feel that they lack formal training in a variety of transferable skills. At Addgene we've set out to fill this gap by both highlighting that researchers do learn MANY transferable skills while working in the lab and by offering advice on areas where you might need some help. Today: Teamwork.

My first experience on a successful scientific team came as an undergrad at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Though some WPI students chose to go the solo route for their Major Qualifying Project (or MQP, the school’s equivalent of a senior thesis), I knew early on that I wanted to work with a partner. WPI’s emphasis on teamwork was what drew me to the school in the first place. The famous discoveries and experiments I’d been learning about for years were usually the products of teams: Watson, Crick, & Franklin, Meselson-Stahl, Hershey-Chase...Who was I to dispute history? And boy did I make the right decision. If I’d spent my senior year isolating pheromones from various C. elegans mutants by myself, I would have slowly gone crazy. As it was, my partner Mike and I split the work, shared the credit, and we both won accolades that would launch our careers in science.

Fast forward nearly 20 years and I am known by some colleagues as the “cross-team guy” at Addgene, an unofficial title that I happily embrace (and admittedly, I may have started that nickname myself). I have my own little Product Management Team, but I’m also an emeritus member of the Scientist Team, a member-by-association of the Development Team, and I contribute to the Management Team that steers the organization. As an Addgene vet familiar with the expertise and skills of many of my colleagues, I can also orchestrate the formation of high-functioning-but-temporary teams that have a specific purpose and finite goals. For example, when it came time to update how we make and distribute kits, I helped assemble a crack team of Addgenies that includes:

- Michelle, the Senior Scientist who coordinates all kit creation and quality control efforts with depositors;

- Gizela, the lab member who knows how the physical kits are made and shipped;

- Chiara, the tech transfer expert who understands the somewhat complicated Material Transfer Agreement process that kits require;

- Nicole, the web master in charge of all our externally facing kit pages.

No single person could possibly understand every nuance of how kits work at Addgene, but with the help of these people and others, we have updated our kit process substantially and have plenty of ideas for further improvements.

Types of teams

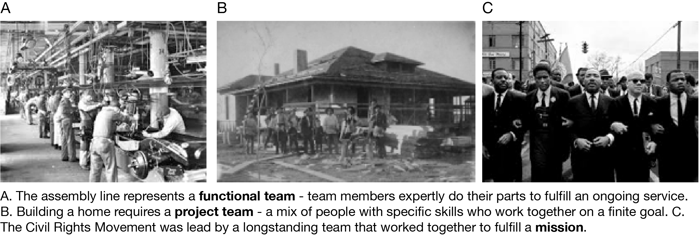

There are, of course, many types of teams. Some teams may be relatively permanent; some teams may only need to exist for a year, or a few months, or even a few weeks. The important thing to remember is that every team should have a goal, or at the very least, a clear reason for existing. Here are a few types of teams that exist at Addgene - team types that could exist anywhere in science:

Functional or process team

A Process Team is a group of people with distinct skills who fulfill a long-term function. When a select group of people are responsible for a group of specific processes, they must work in sync to get tasks done. At Addgene, the Scientist Team is responsible for guiding new deposits into the repository, performing quality control, and providing technical customer service. Team members are highly trained, and though there are necessary redundancies in skills, individuals also tend to have their own specialties. This type of team can exist indefinitely. If you’re looking for this type of team in academia, look no further than your core facilities. If your university is lucky enough to have an imaging core or tissue culture core, you are looking at a process-oriented team serving a particular function.

Project team

A Project Team is assembled to complete a series of tasks with precisely defined goals and endpoints. “Project” is a very broad term since a project goal could be just about anything. Is the goal of your project to launch a product? Make an informed decision about something? Fix a problem? Test a hypothesis? Whether you officially call it a “project team” or not, most scientific collaborations fall within this category. Unlike a process team, you don’t necessarily want a lot of redundant skills - you just want the necessary skills. You might find that your next paper is going to require help from a biochemist, a geneticist, a microscopist, a biostatistician, and that one golden-handed technician who can do a certain difficult assay with her eyes closed. How many times have you ever seen a scientific article attributed to a single author? I’ve seen so few in my 20+ year career that I can’t help but feel a bit dubious when I do come across one. Also, remember, one important feature that all projects have in common - and by association, project teams - is that they come to an end. A project that never ends is a poorly planned project indeed.

Mission team

A Mission Team is assembled to make progress towards open-ended goals whose metrics for success are defined by ongoing mission fulfillment. Earlier this year, I joined Addgene’s Green Team, a like-minded group of co-workers who want to make our organization as environmentally friendly as possible. We worked with Andrew, the team’s founder, to create a mission statement in the first few meetings and we’ve volunteered our ideas, skills, and time to the cause ever since. Unlike the previous two team types, the skills are not cherry-picked. We take what we can get since participation on such a team is strictly voluntary. New members could be recruited, but certainly not conscripted. There’s also no end-game here, unless we manage to make Addgene the most environmentally friendly organization on the planet, in which case whoa! Mission accomplished! One example of a mission-based team in academia would be your school’s post-doc association. And if you’re a post-doc at a school without such an association, start one! These teams can offer a sense of solidarity you’re going to crave.

The benefits of a team

So why is it helpful, or sometimes even necessary, to build a team in the first place? Let’s think about some of the advantages of team-based work:

Nobody knows everything anymore

John F. Kennedy once famously said “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered at the White House - with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.” There was a time in human history when an intelligent, motivated person really could know a little bit about everything or in Jefferson’s case, even a lot about everything. Fast forward a few hundred years and there are currently about 5.5 million articles in the English version of Wikipedia alone. Humans have been forced to specialize in order to deal with all the new information in the world, so a process or project or mission that requires a broad knowledge base is going to necessarily need a diverse group of people to provide that base.

Sometimes there’s just too much work

If you are one of those graduate students putting in 60-80 hours a week in the lab, guess what? You are doing the work of more than one person. A selfish part of you might not want another person’s name on your next paper, but you are not doing yourself or your science any favors by trying to go it alone. The help of fellow lab members and collaborators will not only get your paper out the door much faster, but getting helpful feedback from other people who have a stake in the outcome will ultimately improve the quality of the work as well.

Social interaction is a good thing

Part of you needs to interact with other people, whether you want to acknowledge that or not. I just Googled the phrase “People need social interaction” and received 104 million results (Here’s the top one, in case you’re interested). “But I’m an introvert!” is not an excuse. Every psych test I’ve ever taken has declared me an introvert, and I identify as one. But some time around 10th grade, I snapped out of the phase of my life that had me listening to Simon & Garfunkel’s “I Am A Rock” on repeat in my bedroom. I realized I could and should be interacting more with other people, and becoming part of a team is a really good way of creating and strengthening those social bonds. So never mind how much better your work and productivity will be if you’re part of a team - it will just make you a happier person.

What does a good team need?

Besides that all-important sense of purpose, there are many more things necessary to make a successful team. Entire books have been written about this! But this is a blog post, so here are just a few critical features based on my own experience:

Leadership

Few things are more frustrating than being on a leaderless team. Sometimes the leader just has to be the person to say “OK, guys, we need to have a meeting about this.” Sometimes the common roles of a leader can be successfully doled out to multiple people: someone to coordinate, someone to decide, someone to delegate, etc. If you find that there is not someone (or someones) taking on these responsibilities on a team to which you belong, consider stepping up. Otherwise, you risk putting effort into a team that is doomed to be ineffective.

Defined roles

Though every team should have a leader, other team roles will vary depending on the type of team. Knowing what roles your team requires to function is certainly necessary, but equally important is making sure all team members understand what roles they’re meant to fill and what their responsibilities are. That’s a subtle but important distinction. If I invite someone to be on a project team, I try to make it very clear why that person is there. If it becomes clear after a few meetings that a person is neither adding to the discussion nor getting anything out the discussion themselves, then one has to question whether that person should be on the team. As a team leader, I’ve (diplomatically) booted people off teams. I’ve also kicked myself off of teams when I’ve realized that I really can’t contribute anything. Purging team members does not have to be an act of criticism or judgment - nobody likes to feel useless, and excess people who are not contributing will detrimentally affect a team’s morale and efficiency. You could also just as easily discover you need to add some people if you find there’s a need for an expertise your current team members don’t have - sometimes you just don’t know who you need until the team really starts functioning (or malfunctioning).

Clear lines of communication

Few people actually like meetings, but run well, meetings can be a critical part of any successful team. For reasons I don’t understand to this day, my post-doc adviser almost never had lab meetings. In my nearly 4 years in the lab, we probably didn’t have more than a few dozen lab meetings. The lab, as a team, suffered for it. Nobody knew what anyone else was doing, and there were times when some members really should have been getting feedback from each other. Though meetings are helpful, they are certainly not the only communication options. Addgene, along with an increasing number of academic labs, uses Slack constantly. Whether your teammates are two desks away or on the other side of the world, communication platforms like Slack make teamwork easier.

Trust

Ultimately, your team could have a strong sense of purpose, an excellent leader, and perfectly clear lines of communication, but if teammates don’t trust each other, none of that matters. If you are on a team, any kind of team, and you have nagging doubts that someone else on that team is putting their own self-interest ahead of the team’s goals, then that team is destined to do poorly. To some extent, it doesn’t even matter whether that other person really is acting against the team’s interests or not; once that seed of distrust is planted, it can spread like kudzu. Think of a soccer player who gets a reputation for taking risky shots at the goal rather than going for assists that are more likely to lead to scores. That player doesn’t trust his teammates; the teammates don’t trust him. This team is not going to win games.

The myth of the lone scientist slaving away in a lab to make the Next Great Discovery is exactly that: a myth. The original Dr. Frankenstein from Mary Shelley’s novel worked alone, but even the movie makers saw how absurd this was and gave him an Igor. Science shouldn’t - and really can’t - be done alone. So, if you consider yourself part of the scientific community, get used to the idea of working on teams. Even if you end up on some teams that don’t necessarily work well, you can learn from the experience and make sure your next team works better. In fact, don’t wait to be invited onto a team. Make one yourself. Instead of thinking “What’s my angle on attacking this problem?”, try thinking “Who can I assemble to attack this problem from every angle?” Your science will be better for it.

Additional Resources on the Addgene Blog

- Read other posts in the Transferable Skills Guide

- Management for Scientists: Managing v Leading

- Gain Management Skills Volunteering at a Professional Organization

Resources on Addgene.org

- Check out Career's at Addgene

Topics: Science Careers, Professional Development

Leave a Comment