A recent survey of PhDs found that many researchers feel that they lack formal training in a variety of transferable skills. At Addgene we've set out to fill this gap by both highlighting that researchers do learn MANY transferable skills while working in the lab and by offering advice on areas where you might need some help. Today in our transferable skills guide: Time Mangement for Scientists.

Back when I used to do mammalian cell culture, I would often respond to friends asking me to dinner saying something like, “I’ll be there in a few minutes, I just need to split some cells.” Inevitably, this task would take longer than I thought, I’d be too late to meet up, and I’d just end up spending more time in the lab.

Obviously I didn’t have the best time management skills, but I’ve learned a lot since my days as an undergrad working with cancer cell lines. As I started planning out my own experiments in graduate school, I had to divide my time between lab work and practicing my SciComm skills and I had to coordinate with other people for a variety of projects. I was therefore forced to learn a variety of ways to manage my time. As a busy researcher, you’ve probably already started coming up with time management techniques of your own, but if you ever find yourself in need of a few ideas, I hope you’ll find this post useful.

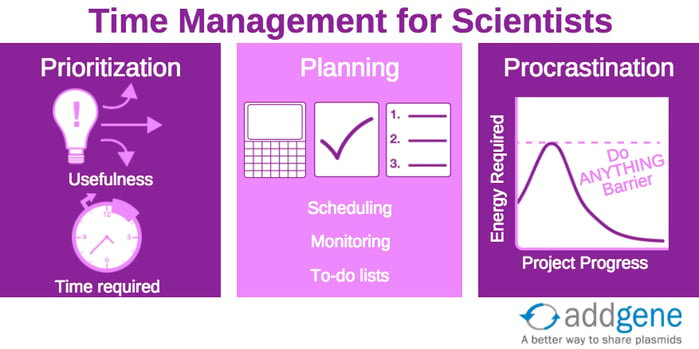

After a bit of research and thinking about my own processes, I’ve broken down time management into three conceptual chunks: prioritization, planning, and procrastination.

Time management through prioritiziation

Every time you begin a task, you’re actively prioritizing. In my anecdote above, I prioritized splitting cells over meeting up with friends, but didn’t realize it until it was too late. I didn’t spend enough time thinking about the possibilities and how to prioritize them.

When deciding what tasks you’re going to take on over the course of the day, month, or even the year, you should be thinking about two main things:

- How useful the task is (its utility)

- How much time it will take you to complete the task

When picking which tasks to actually do, you should err on the side of things that have the most utility; i.e. those things that will be most useful for achieving your goals. However, you should have a good mixture of useful tasks that can be accomplished quickly and things that will take longer. Completing the quick and useful tasks will swiftly give you the wonderful feeling of accomplishment while the longer tasks will give you larger payoffs later.

Don’t be afraid to accomplish some quick but moderately useful tasks at the expense of time spent on the long and highly useful tasks. The quick accomplishments will likely energize you.

For example, let's say you’re doing a multi-day experiment in the lab. You have two ways to set up the experiment. The first way, it will take you 3 days to complete the entire experiment, but you’ll have to spend the entirety of each day doing the experiment. The second way, it will take you 5 days to complete the experiment, but you’ll only spend half of each day on it. The other half of each day you can spend accomplishing small tasks (like... preparing plasmids to send to Addgene). Following my advice from above, you should probably take the second option. Even if the full experiment fails, you’ll still have made small accomplishments each day that should help keep you content and give you the energy to finish any additional work you might need to do.

In most cases, I would recommend the second option for the experiment above, but it’s also important not to load yourself up with too many tasks. If you’re constantly switching between different projects, you might not be able to make any reasonable progress on any one of them. That’s why, as I’ll discuss in the planning section below, it’s important to dedicate specific amounts of time to specific tasks beforehand and assess whether that time was sufficient for the task later. If not, then you should definitely allot more time for that task the next time around.

Finally, when prioritizing, you should always be aware of deadlines and think about what they mean in terms of the utility of your tasks. In my cell splitting anecdote, I probably could have grabbed some food with friends and come back to the lab to split my cells later. Eating with friends has a somewhat immediate deadline - even the best of friends get hangry at some point. My cells, on the other hand, could have waited. Both tasks have some utility, but I lost all the utility (fun) of eating with friends by splitting my cells first.

Time management through planning

I probably wouldn’t have fallen into my cell splitting issue at all if I’d planned appropriately. Back in my undergrad days, I had general goals for my experiments, but didn’t spend enough time thinking about when or how long it would take to achieve these goals. I have far too many projects to operate this way now.

probably wouldn’t have fallen into my cell splitting issue at all if I’d planned appropriately. Back in my undergrad days, I had general goals for my experiments, but didn’t spend enough time thinking about when or how long it would take to achieve these goals. I have far too many projects to operate this way now.

Talking about “planning” is easy, but actually doing it in a productive way can be quite difficult. In my experience, planning has 3 components:

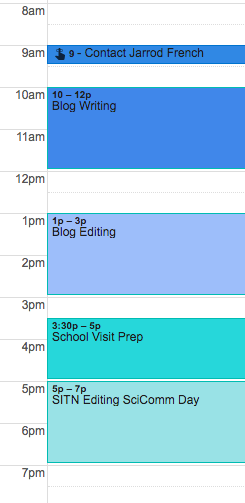

- A mechanism for blocking off time for different tasks. I use google calendar for this and try to give myself flexibility by never placing too many activities too close to one another.

- Monitoring task progress. For this, I always make sure I have explicit goals in mind for the endpoints of a task or project (with metrics if possible) and, at the outset of a task, I outline the activities that are needed to accomplish these goals. Practically speaking, this means I write everything in a Word or google doc that I can comment and make notes on as I progress. I’ve also recently started using Trello to manage larger, multi-person projects.

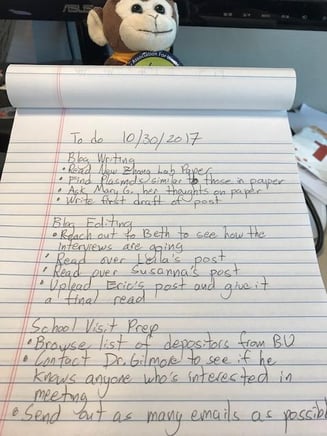

- Day-to-day, flexible to-do lists. Because I know what my goals are (see monitoring task progress), and I know that I’ve blocked out time during my day according to my priorities, I have a pretty good idea about the specific things I’ll be doing through the course of any given week. Knowing this, I hand write to-do lists at the start of each day to remind myself of the specific activities that I need to work on. Throughout the day, I cross items off as they are accomplished or I add to the list as the need arises.

Why do I write things down? It’s more viscerally appealing for me to physically cross things out (it just feels good) and I remember things better when I write them down. Some people also find it useful to write out their to-do lists at the end of the day so they can jump straight into tasks the next day. If you work in a job where you’re pulled in a thousand directions at the start of the day, writing your to-do list the night before will help keep you focused.

For a real-world example, let’s say I’ve blocked out time during my day to write a blog post, edit other blog posts, and contact PIs for an upcoming visit to a university. My to-do list might look something like the image on the right (and for those of you who can’t read my terrible handwriting, is copied below):

For a real-world example, let’s say I’ve blocked out time during my day to write a blog post, edit other blog posts, and contact PIs for an upcoming visit to a university. My to-do list might look something like the image on the right (and for those of you who can’t read my terrible handwriting, is copied below):

- Read new Zhang Lab Paper

- Find plasmids similar to those in the paper

- Ask Mary G. about her thoughts on the paper

- Write first draft of post

- Reach out to Beth to see how the interviews are going

- Read over Leila’s post

- Read over Susanna’s post

- Upload Eric’s post and give it a final read

- Browse list of previous depositors from Boston University

- Contact Dr. Gilmore directly to see if he knows anyone who’s interested in meeting

- Send out as many emails as possible

While accomplishing any one of these things won’t mark an end to the broader project they’re a part of, completing them will give me some sense of accomplishment. I will prioritize which of these items I work on according to how much time I have blocked off for each project and how useful each item is. For instance, if I don’t have draft blog post ready for publication for tomorrow, I’d better upload that post from Eric before doing anything else.

Preventing procrastination

Even if you’ve done all the prioritizing and planning in the world, procrastination can easily prevent you from making progress on a task. For instance, even if I had planned my day extensively, my lack of desire to go sit in the tissue culture hood may have prevented me from splitting cells until late in the day anway. There are a few things I’ve found useful to avoid such procrastination:

- Remove distractions: Probably the easiest way to do this is to leave your phone in your bag on “Do Not Disturb” during the times you’ve blocked out for other activities. This is also part of why I do much of my writing and editing by hand - the internet and all it’s enticements are far too distracting. (As a side note, I’d recommend the book, “Bored and Brilliant” for learning more fantastic reasons to remove yourself from distractions every once in awhile.)

- Reframe the task in a way that highlights the things you like about it. For instance, while I may have found splitting cells boring, hanging out in the tissue culture room also gave me time to listen to some of my favorite podcasts.

- JUST GET STARTED - One Harvard Business Review article on procrastination recommends testing out how much time you can possibly handle doing a particularly annoying task and then dedicating that much time to it each day. Once you get over the activation energy barrier that comes with making ANY progress, the task will likely be much easier. Having a formal plan for your day will make this easier - if you know you have dinner plans at 6 pm, you had better get started early enough to finish everything you need to do by 6 pm.

Hopefully you’ll find this post useful for making your days, experiments, and projects more manageable. If you have any other time management suggestions, please be sure to note them in the comments!

Additional Resources on the Addgene Blog

- Management for Scientists eBook

- Get Advice on Building a Grad Student Community

- Learn about Careers in Science Communication

Resources at Addgene.org

- Check out Careers at Addgene

Topics: Science Careers, Professional Development

Leave a Comment