This post was contributed by Deborah Sweet, Vice President of Editorial at Cell Press.

Almost everyone who works in a lab struggles with reproducibility at some point.

Usually it comes up when a researcher decides on a new project and begins by trying to reproduce someone else’s result. Then, they hit trouble. The experiment won’t work. Even if it does, they don’t get the same result. So, then they end up investing time that they thought would be moving forward instead trying just to get going. It’s like being stuck in jail in Monopoly—you keep rolling the dice and not moving while all your friends are racing around the board. Eventually, you get lucky and manage to escape, but you’ve lost a lot of time.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can never completely eliminate the risk that a minor variation in experimental conditions will derail a research program (think a subtle difference in mouse chow, a different water filtration system, environmental stability in an incubator), but there’s a lot you can do to help other scientists both what you did and build on it going forward. This is not just a question of being honest and straightforward, it’s an important part of being a “good scientific citizen” and making sure you do what you can to help your fellow researchers advance science overall.

Communication is the issue

Much of the problem can be attributed to communication, and in particular communication about experimental methods and approaches. It’s very easy to think that the methods section of a paper is the one that you need to spend the least time on—just put down a basic outline and refer back to the original paper that everyone in your lab has been referencing for the last 10 years, and everything will be fine. It won’t. When we hear about issues with reproducibility, time and time again, the problem comes down to inadequate information about what the original researchers actually did. Admittedly, the differences are often very subtle, and it can take a lot of detective work to figure them out. But, when they come to light, it’s clear that what the researchers thought was a problem in fact was not, and it was just that they were doing something differently.

Communication comes in many forms—from transparency about data to allow others to see what you actually found, to providing reagents in an accessible and consistent way so other researchers can use them, to making sure that methods and protocols are available and detailed enough for someone else to follow them, to being open and willing to share with other researchers to help them troubleshoot and understand. All of this communication and sharing fits together to make for a transparent and collaborative research environment.

Journals as enforcers

Currently, most of the burden for pushing for more transparency in science communication falls on the shoulders of journals and publishers. As journal editors, we often find ourselves having to ask authors for additional information (accession numbers, reagent details, author contributions, etc.) before their paper can be published. To a scientist, all of this checking and formatting can feel like yet another hurdle in front of publication when all they really want to do is get the paper off their desk and move on.

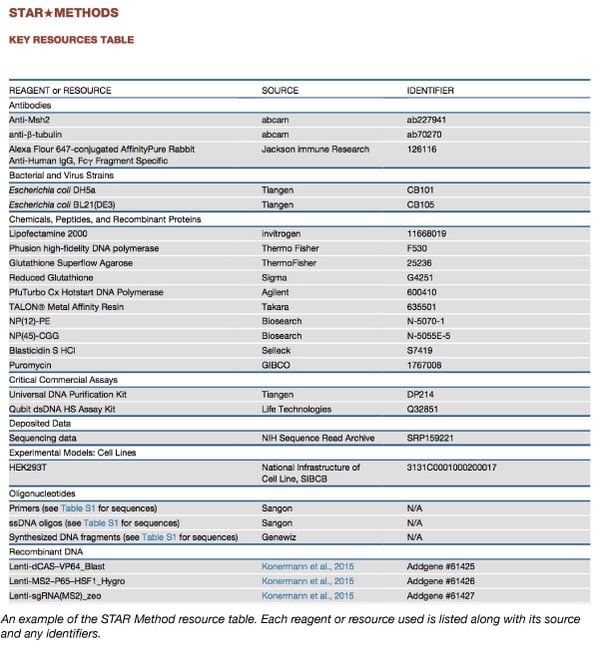

Nevertheless, editors can and do play this role, and we take our responsibility to push for clear communication of science very seriously. That’s why at Cell Press we developed STAR Methods to improve the structure and transparency of methods sections, including clear information about reagents, and why other publishers and organizations have various different versions of checklists and guidelines to help authors understand what they are expected to do. All of that helps, but it’s only a partial solution.

How do we get where we want to be?

How do we get where we want to be?

The part that is still missing is a clear alignment of incentives. Right now, researchers are not strongly rewarded for being transparent in their communication or making their data and reagents readily available. What if that could change? Everyone in science needs both a job and funding, so institutions and funders, to a large extent, hold the keys to getting transparency and communication further up the collective priority list. There has been progress—for example, a number of funders (e.g., the NIH) now look for data management plans and for evidence of sharing for grant renewal—but there is clearly room to do more.

If we could really instill a culture of rewarding good scientific citizenship in all its different forms as part of graduation, hiring, funding, and promotion processes, I’m confident that everyone’s enthusiasm for actually making it happen would increase dramatically. I’m not sure what the best approach to doing that will be, and it will need some effort and experimentation. But it ought to be possible, and if we get it right, everyone in the scientific enterprise will benefit. We’ll have fewer students and postdocs sitting frustratedly in reproducibility jail and more effective collaboration to drive the progress of science.

Sounds like a win for everyone. If we agree we want to get there, that’s half the battle.

Many thanks to our guest blogger Deborah Sweet from Cell Press.

Deborah Sweet is the Vice President of Editorial at Cell Press. She trained originally in cell biology, completing her PhD at the MRC LMB in Cambridge UK and then a postdoc at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. She joined Elsevier after her postdoctoral studies, and has held various editorial roles on review and primary research journals including Trends in Cell Biology, Cell, Molecular Cell, Developmental Cell, and Cell Stem Cell. She was the founding Editor-in-Chief of Cell Stem Cell, a role she held for 10 years, and played a major role in the inception and launch of other Cell Press journals, including Cell Metabolism, Cell Reports and Joule. In September 2017 she moved away from direct editorial work to focus on a broader role as Vice President. Her current responsibilities encompass overall leadership of the Cell Press editorial department, a team of around 100 professional editors who produce a broad range of primary research and review journals across life and physical science, and editorial contribution to the strategic development of Cell Press.

Deborah Sweet is the Vice President of Editorial at Cell Press. She trained originally in cell biology, completing her PhD at the MRC LMB in Cambridge UK and then a postdoc at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. She joined Elsevier after her postdoctoral studies, and has held various editorial roles on review and primary research journals including Trends in Cell Biology, Cell, Molecular Cell, Developmental Cell, and Cell Stem Cell. She was the founding Editor-in-Chief of Cell Stem Cell, a role she held for 10 years, and played a major role in the inception and launch of other Cell Press journals, including Cell Metabolism, Cell Reports and Joule. In September 2017 she moved away from direct editorial work to focus on a broader role as Vice President. Her current responsibilities encompass overall leadership of the Cell Press editorial department, a team of around 100 professional editors who produce a broad range of primary research and review journals across life and physical science, and editorial contribution to the strategic development of Cell Press.

Additional resources on the Addgene blog

- Find more ways to make your research more reproducible

- Read all of our blog posts on scientific publishing

Topics: Scientific Sharing, Reproducibility, Scientific Publishing

Leave a Comment