This post was updated on Jul 27, 2020.

CRISPR, and specifically Cas9 from S. pyogenes (SpCas9), is truly an exceptional genome engineering tool. It is easy to use, functional in most species, and has many applications. That said, SpCas9 is not the only game in town, and other Cas proteins like SaCas9 and Cpf1 can circumvent the limitations associated with SpCas9. Cas13a (previously referred to as C2c2), has several unique properties that further expand the CRISPR toolbox. We'll cover how Cas13a was identified, the structure and function of Cas13a with a focus on what makes this molecule unique, and the various applications of Cas13a.

The origins of Cas13a: An RNA cleaving CRISPR nuclease

Cas13a was originally identified in 2015 (Shmakov et al., 2015). They were using Cas1, a gene commonly associated with CRISPR arrays and involved in spacer acquisition following infection, as a form of “bait” to identify new CRISPR-associated proteins within the bacterial genome. From this analysis, they identified 53 potential candidate genes that fell into 3 categories based on the architecture of the CRISPR protein in question: C2c1, C2c2 and C2c3 (short for Class 2, candidate 1, 2, or 3). C2c1 and C2c3 are related to Cpf1, but they require both a tracrRNA and crRNA to cleave target DNA (Cpf1 requires only a crRNA for target recognition and cleavage). C2c2 (now referred to as Cas13a) is unique in terms of structure and function, and will therefore be the focus of the remainder of this blog post.

Perhaps the biggest difference between Cas13a and Cas9 is that Cas13a binds and cleaves RNA rather than DNA substrates. In terms of structure, Cas13a shares no homology to the most commonly used CRISPR enzymes - Cas13a contains two HEPN domains, whereas Cas9 uses HNH and RuvC domains to cleave target DNA. The HEPN domains within Cas13a are essential for RNA cleavage, consistent with known roles for HEPN domains in other proteins. As with Cas9, mutating key residues in the Cas13a molecule results in a “nuclease dead” Cas13a (dCas13a), that is capable of binding target RNA but lacks the ability to cleave the RNA target.

Table 1: Comparison on Common CRISPR Enzymes

| Name | Enzymatic Domains | Guide RNA | Target | PAM (PFS) | Cleavage Mechanism |

| Cas9 | HNH, RuvC |

TracrRNA, crRNA |

DNA |

5' NGG |

Specific blunt ended DSB in target DNA |

|

Cpf1 |

RuvC-like |

crRNA | DNA | 5' TTN | Specific DSB in target DNA with 5' overhangs |

| Cas13a (C2c2) | 2x HEPN | crRNA | RNA |

3' A, U, or C (not required by all orthologs) |

Specific RNA cleavage (followed by non-specific RNAse activity in bacteria) |

Cas13a targeting with a single crRNA

The Feng Zhang lab used Cas13a from Leptotrichia shahii (LshCas13a) to begin to characterize this new effector (Abudayyeh et al., 2016). In the endogenous CRISPR/Cas9 system, Cas9 uses both a tracrRNA and crRNA to facilitate binding and cleavage of target DNA respectively. LshCas13a, on the other hand, uses only a short ~24 base crRNA that interacts with the Cas13a molecule through a uracil-rich stem loop and facilitates target binding and cleavage through a series of conformational changes in the Cas13a molecule. Like Cas9, Cas13a tolerates single mismatches between the crRNA and target sequence, however cutting efficiency of Cas13a is reduced when 2 mismatches are present. The protospacer flanking sequence (PFS) for LshCas13a, which is analogous to the PAM sequence for Cas9, is located at the 3’ end of the spacer sequence and consists of a single A, U, or C base pair.

In bacteria, once Cas13a has recognized and cleaved its target RNA sequence as specified by the crRNA sequence, it adopts an enzymatically “active” state rather than reverting to an inactive state like Cas9 or Cpf1. As a result, Cas13a will then bind and cleave additional RNAs regardless of homology to the crRNA or presence of a PFS. This is in stark contrast to Cas9, which requires that each DNA target have high sequence identity to the spacer sequence and contain the appropriate PAM sequence. The non-specific cleavage is thought to activate programmed cell death or a dormant state for bacterial cells that have been infected with bacteriophage as to limit the spread of infection throughout the entire population. This property of Cas13a opens up the possibility of using Cas13a as a diagnostic tool, as discussed below.

Subscribe to CRISPR Blog Posts

Applications of Cas13a

|

|

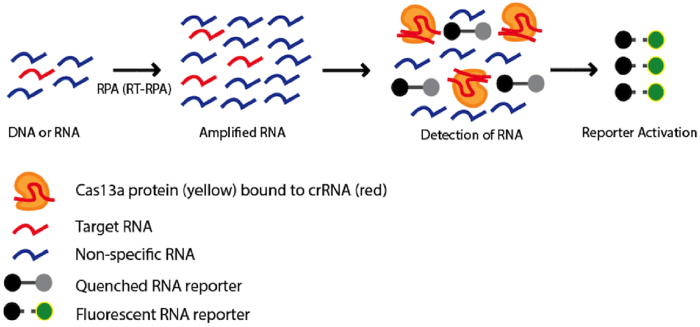

Figure 1: Using Cas13a as a diagnostic tool. A pool of DNA or RNA nucleotides containing a sequence of interest (red) is amplified using Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) or Reverse-transcription RPA (RT-RPA), respectively. Amplified nucleotides are combined with Cas 13a in complex with crRNA targeting the sequence of interest and an inactivated fluorescent RNA reporter. If the target sequence is present in the pool of nucleotides, the nonspecific RNAse activity of Cas13a becomes activated and the RNA reporter will be cleaved resulting in activation of the fluorophore. The fluorescent signal can be used as an indicator to determine whether the target sequence is present in the original pool of nucleotides. |

What are the potential applications of Cas13a given what we know about its structure and function? For starters, Cas13a can be used to bind and cleave target RNAs, although its usefulness in bacterial cells will likely be limited by the propensity of Cas13a to bind and cleave RNA non-specifically. The ability of dCas13a to bind target RNA without cleaving the molecule (like dCas9) suggests that dCas13a may be useful for isolating specific RNA sequences from a population (either enriching or depleting specific RNAs out of a pool of RNAs) or studying RNA processing in live cells. Indeed, groups have utilized dCas13 fusion proteins for imaging, tracking, modulating splicing, and regulating expression of specifically targeted RNAs.

Finally (and perhaps most interesting), Cas13a’s propensity to cleave any RNAs after binding a user-defined RNA sequence could be used to detect single molecules of an RNA species with high specificity (Gootenberg et al., 2017). This system, dubbed SHERLOCK (depicted in figure 1) has been used to differentiate strains of Zika virus, genotype human DNA, identify tumor mutations within cell-free genomic DNA, and detect COVID-19 (Joung, Ladha et al., 2020).

Cas13a in mammalian cells

The Zhang lab made the exciting discovery that some Cas13a orthologs can function in mammalian and plant cells (Abudayyeh et al., 2017). They characterized Cas13a from Leptotrichia wadei (LwaCas13a), using a superfolder GFP fusion to stabilize the protein in mammalian cells. LwaCas13a-msfGFP can mediate cleavage with spacers from 20-28 nucleotides in length and does not require a specific PFS, making it a very flexible cleavage system. LwaCas13a is also amenable to multiplexing; expressing 5 gRNAs simultaneously produces comparable gene knockdown to single gRNA expression.

Although the collateral RNA cleavage response is well described in bacterial cells, LwaCas13a does not display nonspecific RNA cleavage activity in eukaryotic cells. They arrived at this finding through analyses of global RNA expression, cell stress, and RNA size distribution. When comparing LwaCas13a to shRNA, they found that LwaCas13a displays similar knockdown efficiency but no significant off-target effects, a distinct contrast to the hundreds of observed shRNA off-targets. They subsequently used catalytically inactive dLwaCas13a as a programmable RNA-binding protein, creating the fluorescent fusion protein dLwaCas13a-NF for in vivo RNA imaging.

In short, the Cas13a molecule brings a much anticipated element of diversity to the CRISPR toolbox and will continue to expand the applications of CRISPR. Since this post was originally published, we've also seen the new development of Cas13b as a tool for RNA base editing,, and we are excited to see this group of enzymes continue to make a splash in the CRISPR field. We feel that the culture of sharing within the CRISPR community is an essential part of the rapid technology development seen in the field and as always, we appreciate the opportunity to share these invaluable reagents with the scientific community.

Note: Cary Valley and Mary Gearing contributed to the update of this post.

References

1. Abudayyeh, Omar O., et al. "C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector." Science 353(6299) (2016):aaf5573. PubMed PMID: 27256883. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5127784.

- Find plasmids from this paper at Addgene.

2. East-Seletsky, Alexandra, et al. "Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection." Nature 538(7624) (2016):270-273. PubMed PMID: 27669025.

- Find plasmids from this paper at Addgene.

3. Gootenberg, Jonathan S., et al. "Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2." Science (2017): eaam9321. PubMed PMID: 28408723. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5526198.

- Find plasmids from this paper at Addgene.

4. East-Seletsky, Alexandra, et al. "RNA Targeting by Functionally Orthogonal Type VI-A CRISPR-Cas Enzymes. " Mol Cell. 66(3) (2017):373-83. PubMed PMID: 28475872.

- Find plasmids from this paper at Addgene.

5. Abudayyeh, Omar O., et al. “RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13.” Nature 550(7675) (2017):280-284. PMID: 28976959.

- Find plasmids from this paper at Addgene.

6. Shmakov, Sergey, et al. "Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems." Molecular cell 60.3 (2015): 385-397. PubMed PMID: 26593719. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4660269.

7. Joung J, Ladha A, et al., ‘Point-of-care testing for COVID-19 using SHERLOCK diagnostics.’ medRxiv 2020 May 8. Pubmed PMID: 32511521. PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7273289.

- Find plasmids from this paper at Addgene.

Additional Resources on the Addgene Blog

- Check Out Our CRISPR Featured Topic Page

- Learn about Anti-CRISPRs

- Multiplex Genome Editing with Cpf1

Resources on Addgene.org

- Browse All CRISPR Plasmids

- Find Validated gRNAs for Your Next Experiment

- Check Out Our CRISPR Guide Pages

Topics: CRISPR, CRISPR 101, Cas Proteins

Leave a Comment