A 2017 survey found that many researchers feel they lack formal training in a variety of transferable skills. At Addgene, we've set out to fill this gap by both highlighting that researchers do learn MANY transferable skills while working in the lab and by offering advice on areas where you might need some help. Today in our transferable skills guide: Problem-Solving.

I don’t know about your experience in the lab, but mine was plagued by a steady barrage of problems. Why didn’t my PCR work? Why didn’t my ligation work? Why are there so many bands on my Western Blot? Why are there no bands on my Western Blot? Occasionally, there would be an obvious explanation, but more often than not I had to break down exactly what I had done in order to identify potential sources of error and then decide on a strategy to fix the issue. I was problem solving!

You might think that being able to figure out what went wrong with a PCR is a pretty niche skill; outside of a lab, where is that going to come in handy? In fact, all of the problem solving that I did in the lab has been invaluable in my more recent positions outside of the lab. Granted, I currently work on the Scientific Support Team here at Addgene, so troubleshooting molecular biology experiments was in the job description, but this skill is not just about reacting to technical issues. This skill also comes into play while puzzling through your broader research questions and designing future experiments. Being able to work through these types of bigger picture problems systematically and logically is as useful for finishing your thesis as it is for helping your team reach an important milestone at work.

While I was in graduate school and beginning to research non-academic careers, I always felt that descriptions of transferable skills seemed fuzzy or ill-defined. In this article, I try to clarify what people mean when they ask about “problem solving skills” and look at how scientists can develop and highlight these valuable skills. Hopefully, having a better sense for what problem solving entails will help keep you motivated when you’re faced with yet another hurdle in your research journey.

What are ‘problem solving skills’?

As a part of the Scientific Support team, much of my day is spent helping to resolve problems, but even so, I wasn’t sure how to best define this skillset. After sifting through dozens of career advice articles, I settled on defining problem solving skills as:

One’s ability to logically think through a problem/task/situation, come up with potential solutions, and decide on a course of action that effectively resolves the issue.

If this sounds like about seven different skills to you, you are not wrong. Problem-solving overlaps heavily with other skills such as critical thinking, decision making, creativity, or data analysis. Conveniently, these are all skills you are already practicing in the lab.

I like this definition because it helps me see problem solving as a generalizable process.

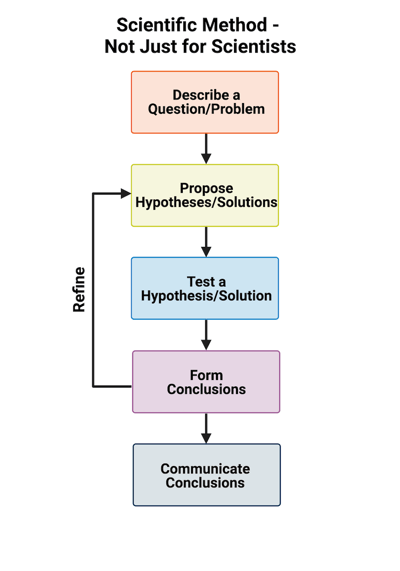

- Step One: Identify the problem and gather information to help you understand it.

- Step Two: Come up with and evaluate potential strategies to resolve the problem.

- Step Three: Decide on a strategy and implement it.

- Step Four: Assess how effective your strategy was. If you didn’t quite fix everything or revealed another issue in the process, you might need to go back to the beginning, reassess the situation, and try a new strategy.

- Step Five: Share your results.

Does this process remind you of anything? Perhaps the Scientific Method? Imagine your problem is just a question you have about the world. You might do some background research to better understand it and come up with several hypotheses on the cause. To test the most likely cause, you implement an experiment designed to fix the problem. Then you assess whether your experiment produced the expected result of resolving the issue. Depending on the particular problem, you might even be expected to write up a report to communicate your findings to your colleagues. So perhaps a better definition of “problem solving skills” is the ability to apply the scientific method to problems in a variety of contexts.

How do you develop problem solving skills?

Thankfully, as scientists, the scientific method is a core part of our academic training. Developing strong problem solving skills is just a matter of applying that framework to the myriad challenges we encounter. As you spend time in a lab learning techniques and taking on independent projects, you will inevitably develop problem solving skills passively. But I have always found that taking a conscious or active approach can be hugely helpful not only for developing a skill but also for being able to recognize it as a part of your skill set later on.

If you are new to research and the lab, you may not be able to carry out the entire problem solving process on your own, but you can start by paying attention to how your mentors reach solutions and ask them to explain their logic. Or you can try applying the scientific method to everyday problems in your life. This tactic is a good way to see how transferable these skills really are, while also practicing systematic, logical thinking.

If you are already a lab veteran at this point, you probably have better developed problem solving skills than you might think. To convince yourself, think back to the last experiment you had to troubleshoot; you probably did not just automatically come to a solution. Consider the thoughts that went through your head as you made observations about the issue, assessed potential protocol modifications, and ultimately decided on the changes to implement. As with any skill, there will always be room to improve. The next time you face a problem, try to be mindful of how you work through it. Ask yourself if you missed any important details. Or challenge yourself to think of more creative solutions. Ultimately, problem solving is less about technical know-how and more about how you approach new challenges.

Know your strengths!

Research experience presents ample opportunities to practice problem solving skills and learn to apply them flexibly in a range of contexts. As such, scientists are uniquely prepared to be strong problem solvers both in and out of the lab. The next step is to remember that you have these skills when you start applying and interviewing for new positions. Highlighting your problem solving skills can help convince a future employer that you are well equipped to work through challenges from day one in your new position. Of course, there are limits to how far strong problem solving skills alone can take you - just because I can resolve issues effectively does not mean I am qualified to be an astronaut. But, knowing that this skillset is a part of your toolkit is important. Paired with your other skills, both technical and transferable (i.e. teamwork and time management), your ability to solve problems efficiently and effectively will help you grow in whatever career path you choose.

Resources

Additional resources on the Addgene blog

- More from the transferable skills guide:

Resources on Addgene.org

- Check out our careers page

- Watch our career videos

Topics: Science Careers, Professional Development

Leave a Comment