Finding research papers is not particularly hard. There are millions of them. The real challenge is finding relevant papers. The latest installment of the Early Career Researcher Toolbox will highlight four tools for finding journal articles related to your actual interests while also staying on top of the ever expanding body of biomedical literature!

Finding research papers is not particularly hard. There are millions of them. The real challenge is finding relevant papers. The latest installment of the Early Career Researcher Toolbox will highlight four tools for finding journal articles related to your actual interests while also staying on top of the ever expanding body of biomedical literature!

PubMed

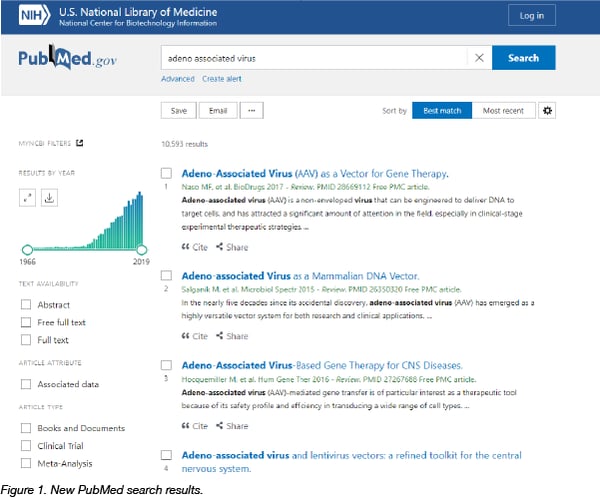

PubMed is the classic search engine for finding papers. It’s been around since 1996, but is getting an update! The latest version can be found here. The new PubMed will become the default PubMed search option in early 2020 and eventually replace the existing version of PubMed.

Key features

This new version has an improved search algorithm which was trained on key factors from past PubMed user searches, such as clicks to read the abstract or full text of the paper, publication date, a relevance score, and type of article. Now, search results display a bar graph of the number of papers with your search term published each year, which is a nice way to see growth or decline of interest in a field over time. Creating an alert for a search term helps automate your search for new papers. An alert lets you receive a daily, weekly, or monthly digest of newly published papers that contain that term. You can also set up alerts for new publications from a particular author.

Saving papers

Papers can be saved to a collection, which is essentially a virtual bookshelf.

Pro tip

The “cited by” and references sections of a PubMed entry are great places to look for more articles on your topic of interest.

Best uses

Accessing the vast body of biomedical research papers.

Scientists often use Twitter to promote their work, so it’s also a good place to look for publications. Bonus: papers have to be summarized in 280 characters!

Using Twitter to find papers

You’ll need to start following relevant accounts in order to turn Twitter into a paper-finding-machine. There are four general types of accounts you can follow:

- Scientists: Following other scientists helps you stay on top of what others are studying and gives you a sense of what people are excited about. Following scientists in fields outside your main research focus lets you keep a pulse on what’s going on in other areas of science. Scientists often post tweetorials, or threaded summaries, of their papers. These are a great resource for getting a quick summary of papers before investing the time to read them.

- Organizations: Accounts for nonprofits, research organizations, and universities often tweet about publications in the fields of research they support. Monitoring these types of accounts can help you find papers related to a particular topic or that were published by the lab down the hall.

- Scientific journals: They publish papers, so naturally they tweet about papers too. You can follow journals related to your field of research or larger journals that publish about a broad range of topics.

- Twitter paper bots: Twitter bots tweet posts that contain specific keywords. It’s sort of like a keyword search that’s constantly updated. This Twitter list contains >300 Twitter literature bots, including a bot for biosensor papers, microbe articles, CRISPR papers, and more.

Saving papers

There isn’t technically a way to save papers on Twitter, but you can bookmark a tweet in order to easily access it later.

Pro tip

Checking the number of retweets, likes, and comments on a tweet about a paper can help you gauge how “hot” a paper is.

Best uses

Finding recent papers that the scientific community is talking about and jumping into the discussion!

Semantic Scholar

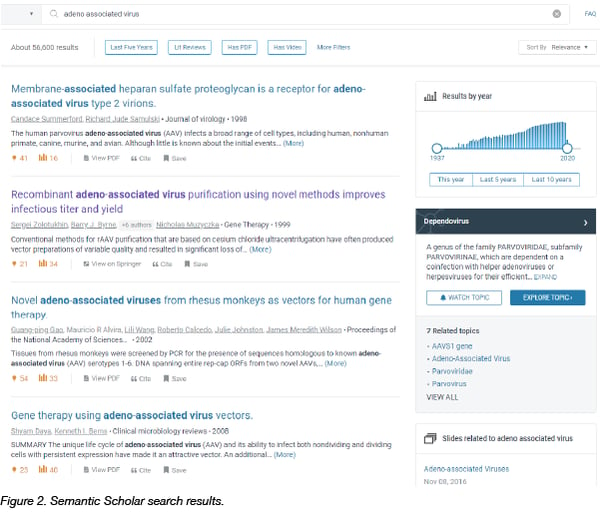

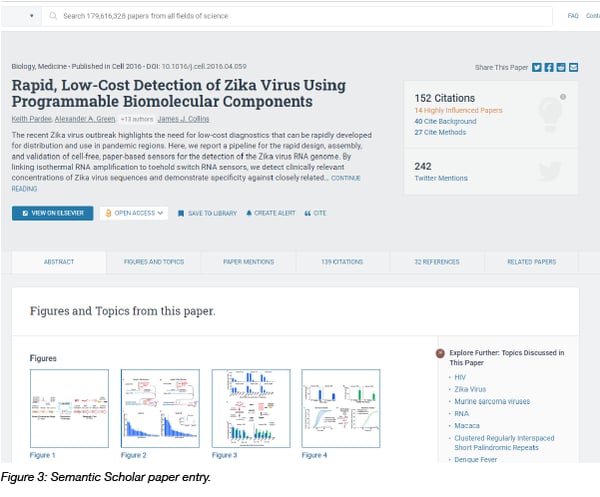

Semantic Scholar is an AI-backed literature search developed by the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. Semantic Scholar analyzes publications and figures using machine learning to extract important features such as influential citations, images, and key phrases. It also takes into account how papers are connected via citations, in order to return results that are more relevant to your search terms.

Key features

Semantic Scholar has several ways to focus your search results. A bar graph of the number of papers with your key term published each year is displayed with your search results and can be used to filter your search to a specific window of time for publication. To help you quickly identify papers with greater influence, the average number of citations per year and the number of other manuscripts that heavily cite the paper are displayed. You can also limit searches to particular authors, with the authors who published the most papers with your keyword populated at the top of this filter. A unique feature of Semantic Scholar search results are the topic pages, which contain a short summary of the topic and a chronological list of highly cited papers that contain your search term.

When you view a paper’s entry, the number of citations that paper has is displayed at the top of the page, as well as the number of citations highly influenced by this paper. Influence is measured by the number of citations and the context of these citations. The number of manuscripts that cite the background, methods, or results section is also displayed.

Saving papers

Papers can be saved to a Semantic Scholar library. You can add hashtags to library entries, which can help you organize and search for papers later.

Pro tip

Learn more about authors by exploring author pages (for example, Melina Fan’s author page). These pages show all publications by an author, total number of citations, and the number of publications that heavily cite, or are highly influenced by the author. You can also see who an author is most influenced by (other authors who they cite the most), and who the author influences (who cites the author the most).

Best uses

Finding papers frequently cited by others. This is a great hack for finding relevant papers even if you aren’t familiar with the topic.

Meta

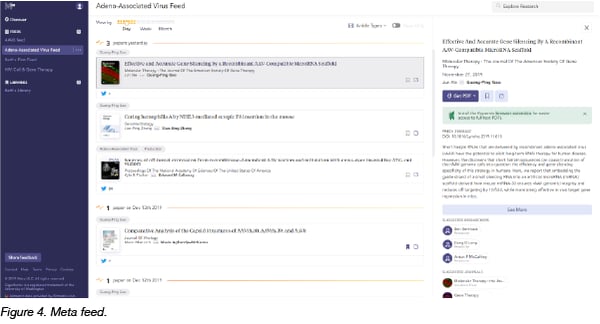

Meta is a literature discovery platform developed by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Meta is not a traditional search engine. Instead, you create your own research feed by entering keywords, concepts, journals, and/or papers of interest. You can also just follow feeds curated by Meta. Feeds automatically update as papers are published, similar to Facebook or Instagram.

Key features

Setting up a personalized feed is simple. You can enter as many search terms as you like, and your feed will update with new papers that contain these terms. You can also create intersects in your feed which means only papers than contain all of your search terms will show up in your feed. Feeds are organized by papers published each day, week, or month. A measure of the number of times a paper is shared online, or its altmetric score, is also displayed in your feed. By clicking on a paper in your feed you can see suggested related researchers, journals, and concepts to help you expand your search. Results in your feed are ranked based on their influence on the network, or body of literature, as a whole.

Saving papers

Papers are easily saved to a Meta library. The library will suggest additional papers based on the papers you have saved. This library can also be synced with a Mendeley reference manager account.

Pro tip

Sign up for weekly email digests of the top papers in your feed. This is a great way to have new papers delivered directly to your inbox.

Best uses

Staying up-to-date on new publications in your field. Feeds are constantly updated, so you’ll never miss a new paper.

Though we only covered four ways to find relevant papers in the post, there are many more ways out there. Let us know if you if you have any favorite tips and tricks for navigating the always growing sea of scientific literature.

Additional resources on the Addgene blog

- Learn why scientists should be on Twitter

- Read our Early Career Research Toolbox blog posts on free tools for making scientific graphics post and social media for scientists

Topics: Science Careers, Early Career Researcher, Scientific Publishing

Leave a Comment